Artists Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst Send A.I. Mutants to the Whitney Biennial

The married artist duo are proponents and cautious prognosticators of A.I. Their distorted hirsute mutant warrior has become an avatar for the 2024 Whitney Biennial.

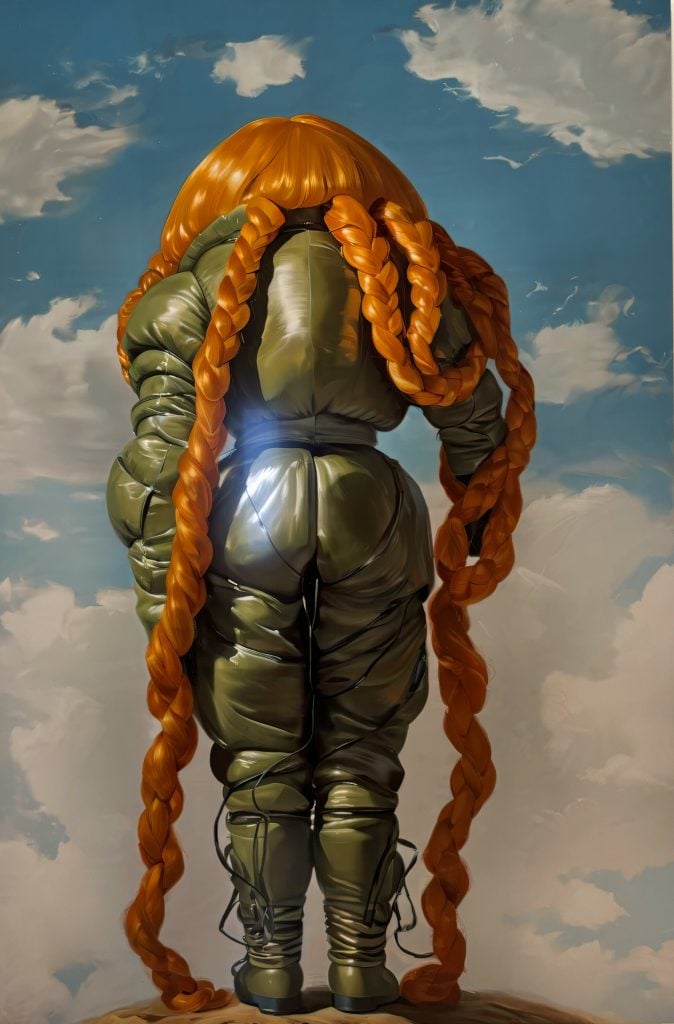

When the elevator opens to the 6th-floor entrance of this year’s Whitney Biennial, the first thing you’ll see is a door-sized print depicting the back of a cartoonish character in a puffy suit and a helmet of hair. On a nearby wall is a frontal portrait of the same figure, fists clenched, a determined expression on her face. She looks like some futuristic soldier en route to an unseen war.

This is the work of the Berlin-based husband-and-wife duo Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst. Well, sort of: the paired portraits were produced by an AI model they developed for the show. That’s a distinction inherent to many of the projects made by these collaborators; they create systems that create content. And it wasn’t until recently that this content took the form of visual art. The technically-minded duo are more well-known in the world of experimental music. They’ve studied and taught at progressive schools, made glitched out and critically-acclaimed albums (under Herndon’s name), and even opened for Radiohead. The computer has almost always been at the center of their sound; their instruments are made of code, not wood and metal.

Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst, xhairymutantx, Embedding Study 1, (2024). Photograph by Audrey Wang.

In more recent years, Herndon and Dryhurst’s penchant for interrogating newfangled forms of technology and the language of theory developing around them has pushed their work toward something that more resembles both conceptual art and digital activism. In 2021, they developed Holly+, a program that allows musicians to perform using a deepfake version of Herdon’s voice. (They demonstrated the tool in a TED Talk, then used it to cover Dolly Parton’s Jolene.) In 2022, they partnered with Jordan Meyer and Patrick Hoepner to launch Spawning, a website that enables artists to remove their work from datasets used to train AI models.

With projects like these, and through their four-year-old podcast, Interdependence, Herndon and Dryhurst have taken on dual roles as advocates and educators operating on the bleeding edge of shifting discourses around consent, intellectual property, and identity in a web 3.0 world. Their efforts are rangy and idiosyncratic, and yet they’ve earned a rather narrow reputation. At the Whitney Biennial and beyond, these are two defining faces of AI art.

That’s particularly true for Herndon (she was included in TIME’s inaugural “Most Influential People in AI” list last year), and it’s not just because she tends to be the more forward-facing of the two. The Tennessee native has a doll-like face punctuated by Lapis lazuli eyes and long, carrot-orange hair that’s almost always styled the same way: blunt bangs in the front, Rapunzelly braids in the back. She is striking, kind of uncannily so. Her defining colors are almost too complimentary, her features too familiar. Even before the development of commercial text-to-image generators, photos of Herndon looked like they were made by AI.

That wasn’t actually the case. But it may be soon.

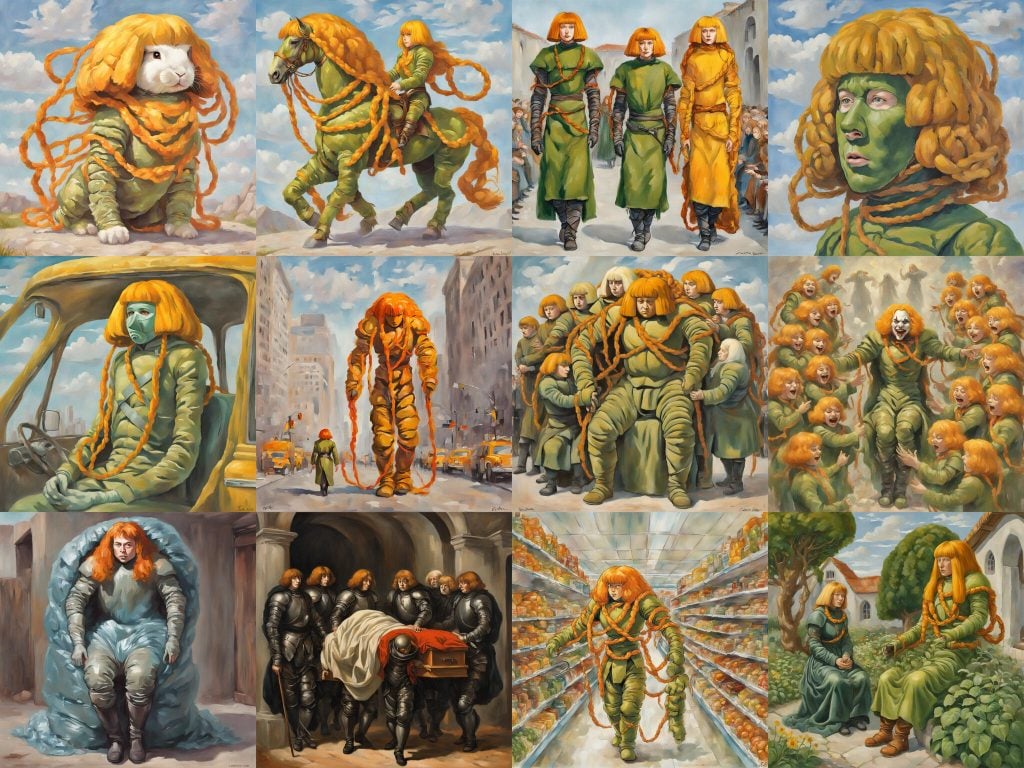

A selection of images generated by Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst’s xhairymutantx (2024).

Herndon’s distinct features and moderate fame make her an easy input for generative programs like DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion. Type in her name and these apps will produce a picture that actually looks like her. But Herndon herself has no control over what she is made to look like—and that’s a problem. These “models are supposed to be objective, but there’s no such thing,” she said. “Your idea of a cup is different from my idea of a cup. And when it comes to individuals, and the way that you want to present yourself online, how much agency do we have in that?”

During the web 2.0 era, we willingly fed Facebook, Twitter, and other commercialized platforms our images. The prospect was too good to resist: these apps were free and we could use them to craft our own idealized online avatars. But now, the British-born Dryhurst wrote in a 2023 ArtReview essay, “We are witnessing the revenge of free media; the business end of that Faustian bargain.” In this new era of AI, we have lost control over our online appearance.”

Dryhurst and his partner are working to get it back. The program they built for the Biennial was trained on images of Herndon, but not the kind you’ll find online. Instead, they fed it a series of bizarro portraits in which the artist’s physical attributes had been exaggerated to the point of absurdity. “I’m this hulking haircut,” Herndon joked, then added that the name of the project tips us to the kind of pictures it produces: xhairymutantx.

The artwork also goes beyond the museum’s walls. xhairymutantx is hosted on the Whitney’s artport website and is both free and easy to use. As with other AI tools, you just type in a phrase and it will generate a picture. In this case, though, the result will almost always feature at least some abstract vestiges of the mutant Holly. The prompt “Boston Terrier playing keytar in outer space” yielded an image powerful enough to end all human suffering, but the picture has its oddities too: the dog is wearing that puffy suit and his instrument is powered by cables of Herndon’s hair.

Boston Terrier playing keytar in outer space by Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst.

The goal is to produce enough user-generated images of Herndon to distort existent data sets, so that in the future, if someone uses a text-to-image app to create a picture of her, it will look like the monstrous version she chose, not the amalgamated one chosen by the model. That would be great, but it would also mean that generated portraits of Herndon will continually integrate these grossly exaggerated features. If control over your image is the aim, wouldn’t you want to work with flattering pictures of yourself?

Alas, that’s the rub. “We thought about totally changing my appearance, making me into a purple octopus or something,” explained Herndon. “But if the thing you’re introducing into this point cloud is so different, the model ignores it.” The irony is plain as day, Dryhurst points out: “If Holly wants to transform herself, she has to become more of a cliche.”

So to achieve some sense of self determination in these AI systems, you have to play by the systems’ rules. That’s not ideal, but it is a start. And in reality, the impact of xhairymutantx doesn’t hinge on its ability to skew data sets. This project is meant to direct people’s attention to the problem, not provide the solution. The fact of the matter is that right now, there is no effective solution. “You could sell an emancipatory vision of having agency over how you appear in models, and I do hope that we will get there,” said Dryhurst, “but currently you do not have agency.”

And xhairymutantx points in broader directions too. “I think it really highlights the systems that govern us,” said curator Meg Onli, who co-organized the Biennial with Chrissie Iles. Inside the show, a section of wall text lays out the curators’ aims, but it could have been written specifically about Herndon and Dryhurst’s contributions: “The exhibition’s subtitle, Even Better Than the Real Thing, acknowledges that Artificial Intelligence (AI) is complicating our understanding of what is real, and rhetoric around gender and authenticity is being used politically and legally to perpetuate transphobia and restrict bodily autonomy.”

There has been a tremendous amount of skepticism around AI in recent years, much of it from people who see the technology in scare quotes. Their distrust is not wholly unjustified, and many who are hyper-educated on the topic tend to agree that AI is primed for misuse and unintended consequences lest we establish ethical and legal fences around it. Among those advocating for change, there are two camps: those who want to alter it within, and those who want to blow it up and create something new. Herndon and Dryhurst unequivocally belong to the former. They have come to the conclusion that, in Dryhurst’s words, we are “far better off trying to make interventions inside the tent.” That tent may be filled with mutants for a while, but it’ll be far less scary than the one we’re living in now.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: